|

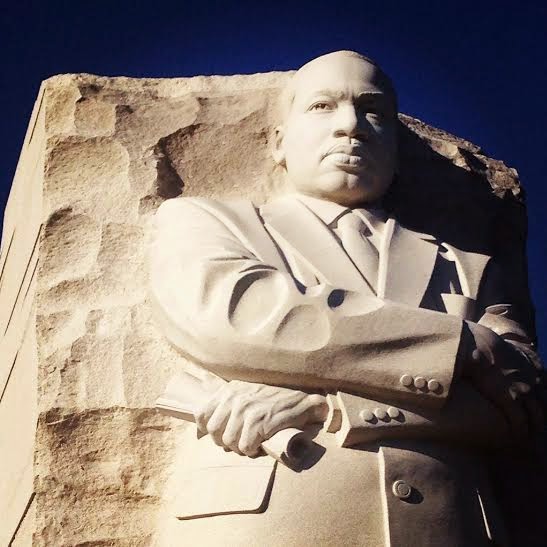

| MLK Memorial, DC - November 2014 |

The conversation on race relations in America has been difficult for me to engage with over the past months following #Ferguson. I have felt and continue to feel compelled to join the struggle for improvement in our country, however, institutionalized racism and white privilege have created a barrier even in the way we, white people and people of color, can positively effect change (eg: link to 12 Ways to be a White Ally to Black People by Janee Woods). After a 3 month sabbatical at home, I feel more closely connected to this topic and would like to express some thoughts, albeit they are constantly changing as this wider conversation evolves.

Since the death of Mike Brown and the following months of protest in #Ferguson and beyond, the United States has seen a re-emergence of conversations around issues of race, poverty, equality and justice. Subsequent cases of police brutality, including the death of Eric Garner, resulted in further demonstration such as the "No Justice, No Tree" protests outside of the Rockefeller lighting of the Christmas tree in New York city in December 2014.

The impact of increased civic mobility following these events can be seen in the wider conversation taking place across the US and beyond via social media and other outlets, meetings among key stakeholders to propose and plan for change, and broader engagement throughout society. It will take time to see the long-term impacts of these efforts, however, it can already be noted that the hands up Twitter movement and other mobilization taking place across the country have been a great success in raising awareness around serious issues while including people who have often been marginalized into the struggle.

In the Midterm Elections of November 2014 I worked as an election official in Annapolis, Maryland in a socially diverse electoral district. Anecdotally, a co-worker who as born and bred in a majority African American neighborhood in our district, made note that there were a lot of people missing from his own area who could have come out to vote. When I asked him why he didn't call them to come down, he said it wasn't his responsibility to tell people what to do. I understood his meaning and didn't press the question further.

When the ballots were counted and Republican representatives won by overwhelming majorities, including in my own traditionally Democratic state of Maryland, people were not surprised. Some people, like myself, were saddened by what this change would mean in the face of the deepening schisms within the country, fighting polarised battles around sensitve topics such as immigration, health care and police reform.

Immediately we turned our attentions to the low turn out at the polling stations across the country, including the two-thirds of African Americans who did not vote (link to Reflections on the 2014 Midterm Elections by Clarence B. Jones)

and the overwhelming abstention of youth voters, who in some states dropped by 20% from 2010 (link to CIRCLE article on Youth Turn-Out). This low turn-out following increased civic activity across the United States seems difficult to understand at first glance. Why wouldn't people vote if they wanted change?

Just before leaving my hometown to return to Belfast, I went to see Selma, knowing it was a film made in tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but very little about the premise. I came to find that although I've studied American History and taken courses exclusively dedicated to African American history, although I grew up in a border state with history of slavery and racial persecution, and although I engage actively and openly with conversations around race and equality, I do not, and possibly cannot understand the "terror of living in the south" as an African American during the times of MLK (link to Most of you have no idea what Martin Luther King actually did by Hamden Rice).

When I left the film Selma I wondered why it didn't come out sooner, wishing it had been released before the elections to remind many of us in pursuit of change but who did not use our vote of the lives lost in the fight for voting privileges. I left the cinema feeling inspired by the faith and hope people maintained during such trying times, marching alongside MLK and one another and continuing to register to vote while knowing the persecution they could face. I also left feeling helpless after witnessing the suffering so many Americans, particularly Black Americans, have faced in this struggle and the continued challenges that institutionalized racism present in the everyday life of so many.

Upon further reflection, I understand more clearly why so many people did not vote. There are more nuanced analyses of this issue available, but to me it seems clear. There is no hope that change will come once we vote. People do not feel inspired to work within a system that feels broken. A system that continues to function alongside blatant injustice. A system that is biased. To add insult to injury, instances of racial injustice are occurring alongside the second term of our first Black president, a constant and very real reminder that positive change is a slow and tiring process.

Living in Northern Ireland after the Troubles, a conflict which was also fueled by the Civil Rights movement, I am becoming more familiar with the struggles that took place here to overcome the destruction of hope resulting at the hands of injustice, inequality, institutionalized prejudice, police brutality and community aggression and the subsequent mistrust between the two. Polarized politics have brought government to a standstill, in some cases literally dissolving the institutions built to serve.

These similarities go to show that the impacts of oppression and injustice will linger long after physical violence is abated. In the words of MLK, "We must concentrate not merely on the negative expulsion of war but the positive affirmation of peace". This includes justice for all.

Ultimately, we need hope for a better future and a trust in the political process that enforces democratic change. If people felt their representatives could hear and respond to their needs, they would vote. In the last few months, polarized politics, cases of questionable impunity and lack of empathy among us all have caused further deterioration to an already divided system. For the next 4 years, many states will have politicians who do not reflect the will of their constituents, because people have lost faith in the system.

Continued dialogue and grassroots efforts working for justice and change will be the way forward in the coming years. We all have a role to play, regardless of our class, color or creed. By maintaining and broadening the heightened levels of participation that we've built upon in the past months, we can continue to find effective ways to speak, protest and work together.